This article is about a decorative art. For other uses, see Mosaic (disambiguation).

Irano-Roman floor mosaic detail from the palace of Shapur I at Bishapur. |

cone mosaic courtyard from

Uruk in

Mesopotamia 3000 B.C.

Fur mosaic with portrait of

Emperor Franz Joseph Mosaic is the art of creating images with an assemblage of small pieces of colored glass, stone, or other materials. It may be a technique of decorative art, an aspect of interior decoration, or of cultural and spiritual significance as in a cathedral. Small pieces, normally roughly cubic, of stone or glass of different colors, known as tesserae, (diminutive tessellae), are used to create a pattern or picture.

History of the Mosaic

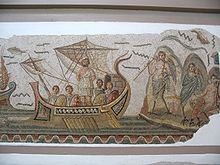

Roman mosaic of

Ulysses, from Carthage. Now in the

Bardo Museum,

Tunisia

Cave canem mosaics ('

Beware of the dog') were a popular motif for the thresholds of

Roman villas

A small part of

The Great Pavement, a Roman mosaic laid in AD 325 at

Woodchester,

Gloucestershire, England.

The earliest known examples of mosaics made of different materials were found at a temple building in Ubaid, Mesopotamia, and are dated to the second half of 2nd millennium BC. They consist of pieces of colored stones, shells and ivory. Excavations at Susa and Choqa Zanbil show evidence of the first glazed tiles, dating from around 1500 BC.[1] However, mosaic patterns were not used until the times of Sassanid Empire and Roman influence.

Mosaics of the 4th century BC are found in the Macedonian palace-city of Aegae and they enriched the floors of Hellenistic villas, and Roman dwellings from Britain to Dura-Europos. Splendid mosaic floors are found in Roman villas across north Africa, in places such as Carthage, and can still be seen in the extensive collection in Bardo Museum in Tunis, Tunisia. In Rome, Nero and his architects used mosaics to cover the surfaces of walls and ceilings in the Domus Aurea, built AD 64.

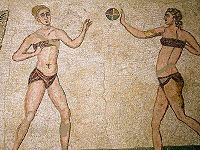

The mosaics of the Villa Romana del Casale near Piazza Armerina in Sicily are the largest collection of late Roman mosaics in situ in the world, and are protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The large villa rustica, which was probably owned by Emperor Maximian, was built largely in the early 4th century. The mosaics were covered and protected for 700 years by a landslide that occurred in the 12th century. The most important pieces are the Circus Scene, the 64 m long Great Hunting Scene, the Little Hunt, the Labours of Hercules and the famous Bikini Girls, showing women exercising in modern-looking bikinis. The peristyle, the imperial apartments and the thermae were also decorated with ornamental and mythological mosaics. Other important examples of Roman mosaic art in Sicily were unearthed on the Piazza Vittoria in Palermo where two houses were discovered. The most important scenes there depicted Orpheus, Alexander the Great's Hunt and the Four Seasons.

Mosaics of girls in bikinis at the Villa Romana

In 2000 archaeologists working in Leptis Magna, Libya uncovered a 30 ft length of five colorful mosaics created during the 1st or 2nd century. The mosaics show a warrior in combat with a deer, four young men wrestling a wild bull to the ground, and a gladiator resting in a state of fatigue, staring at his slain opponent. The mosaics decorated the walls of a cold plunge pool in a bath house within a Roman villa. The gladiator mosaic is noted by scholars as one of the finest examples of mosaic art ever seen — a "masterpiece comparable in quality with the Alexander Mosaic in Pompeii."

Christian mosaic

Early Christian art

Main article: Late Antique and medieval mosaics in Italy

With the building of Christian basilicas in the late 4th century, wall and ceiling mosaics were adopted for Christian uses. The earliest examples of Christian basilicas have not survived, but the mosaics of Santa Constanza and Santa Pudenziana, both from the 4th century, still exist. The winemaking putti in the ambulatory of Santa Constanza still follow the classical tradition in that they represent the feast of Bacchus, which symbolizes transformation or change, and are thus appropriate for a mausoleum, the original function of this building. In another great Constantinian basilica, the Church of the Nativity in Betlehem the original mosaic floor with typical Roman geometric motifs is partially preserved. The so-called Tomb of the Julii, near the crypt beneath St Peter's Basilica, is a fourth-century vaulted tomb with wall and ceiling mosaics that are given Christian interpretations. The former Tomb of Galerius in Thessaloniki, converted into a Christian church during the course of the 4th century, was embellished with very high artistic quality mosaics. Only fragments survive of the original decoration, especially a band depicting saints with hands raised in prayer, in front of complex architectural fantasies.

In the following century Ravenna, the capital of the Western Roman Empire, became the center of late Roman mosaic art (see details in Ravenna section). Milan also served as the capital of the western empire in the 4th century. In the St Aquilinus Chapel of the Basilica of San Lorenzo, mosaics executed in the late 4th and early 5th centuries depict Christ with the Apostles and the Abduction of Elijah; these mosaics are outstanding for their bright colors, naturalism and adherence to the classical canons of order and proportion. The surviving apse mosaic of the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio, which shows Christ enthroned between Saint Gervasius and Saint Protasius and angels before a golden background date back to the 5th and to the 8th century, although it was restored many times later. The baptistery of the basilica, which was demolished in the 15th century, had a vault covered with gold-leaf tesserae, large quantities of which were found when the site was excavated. In the small shrine of San Vittore in ciel d'oro, now a chapel of Sant'Ambrogio, every surface is covered with mosaics from the second half of the 5th century. Saint Victor is depicted in the center of the golden dome, while figures of saints are shown on the walls before a blue background. The low spandrels give space for the symbols of the four.

Albingaunum was the main Roman port of Liguria. The octagonal baptistery of the town was decorated in the 5th century with high quality blue and white mosaics representing the Apostles. The surviving remains are fragmentary.

A mosaic pavement depicting humans, animals and plants from the original fourth-century cathedral of Aquileia has survived in the later medieval church. This mosaic adopts pagan motifs such as the Nilotic scene, but behind the traditional naturalistic content is Christian symbolism such as the ichthys. The sixth-century early Christian basilicas of Sant' Eufemia it:Basilica di Sant'Eufemia (Grado) and Santa Maria delle Grazie in Grado also have mosaic floors.

Ravenna mosaic

In the 5th century Ravenna, the capital of the Western Roman Empire, became the center of late Roman mosaic art. The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia was decorated with mosaics of high artistic quality in 425-430. The vaults of the small, cross-shaped structure are clad with mosaics on blue background. The central motif above the crossing is a golden cross in the middle of the stary sky. Another great building established by Galla Placidia was the Church of San Giovanni Evangelista. She erected it in fulfillment of a vow that she made having escaped from a deadly storm in 425 on the sea voyage from Constantinople to Ravenna. The mosaics depicted the storm, portraits of members of the western and eastern imperial family and the bishop of Ravenna, Peter Chrysologus. They are only known from Renaissance sources because they were destroyed in 1569.

Ostrogoths kept alive the tradition in the sixth century, as the mosaics of the Arian Baptistry, Baptistry of Neon, Archiepiscopal Chapel, and the earlier phase mosaics in the Basilica of San Vitale and Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo testify.

After 539 Ravenna was conquered by the Byzantine Empire and became the seat of the Exarchate of Ravenna. The greatest development of Christian mosaics unfolded in the second half of the 6th century. Outstanding examples of Byzantine mosaic art are the later phase mosaics in the Basilica of San Vitale and Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo. The mosaic depicting Emperor Justinian I and Empress Theodora in the Basilica of San Vitale were executed shortly after the Byzantine conquest. The mosaics of the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe were made around 549. The anti-Arian theme is obvious in the apse mosaic of San Michele in Affricisco, executed in 545-547 (largely destroyed, the remains in Berlin).

The last example of Byzantine mosaics in Ravenna was commissioned by bishop Reparatus between 673-79 in the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe. The mosaic panel in the apse showing the bishop with Emperor Constantine IV is obviously an imitation of the Justinian panel in San Vitale.

Butrint mosaic

The mosaic pavement of the Vrina Plain basilica of Butrint, Albania appear to pre-date that of the Baptistery by almost a generation, dating to the last quarter of the 5th or the first years of the 6th century AD. The mosaic displays a variety of motifs including sea-creatures, birds, terrestrial beasts, fruits, flowers, trees and abstracts – designed to depict a terrestrial paradise of God’s creation. Superimposed on this scheme are two large tablets, tabulae ansatae, carrying inscriptions. A variety of fish, a crab, a lobster, shrimps, mushrooms, flowers, a stag and two cruciform designs surround the smaller of the two inscriptions, which reads: In fulfilment of the vow (prayer) of those whose names God knows. This anonymous dedicatory inscription is a public demonstration of the benefactors’ humility and an acknowledgement of God’s omniscience.

The abundant variety of natural life depicted in the Butrint mosaics celebrates the richness of God’s creation; some elements also have specific connotations. The kantharos vase and vine refer to the eucharist, the symbol of the sacrifice of Christ leading to salvation. Peacocks are symbols of paradise and resurrection; shown eating or drinking from the vase they indicate the route to eternal life. Deer or stags were commonly used as images of the faithful aspiring to Christ: ‘like a hart desires the water brook, so my souls longs for thee, O God.’ Water-birds and fish and other sea-creatures can indicate baptism as well as the members of the Church who are christened.

Butrint is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Late Antique and Early Medieval Rome mosaic

See also: Late Antique and medieval mosaics in Italy

Christian mosaic art also flourished in Rome, gradually declining as conditions became more difficult in the Early Middle Ages. Fifth-century mosaics can be found over the triumphal arch and in the nave of the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. The 27 surviving panels of the nave are the most important mosaic cycle in Rome of this period. Two other important 5th-century mosaics are lost but we know them from 17th-century drawings. In the apse mosaic of Sant'Agata dei Goti (462-472, destroyed in 1589) Christ was seated on a globe with the twelve Apostles flanking him, six on either side. At Sant'Andrea in Catabarbara (468-483, destroyed in 1686) Christ appeared in the center, flanked on either side by three Apostles. Four streams flowed from the little mountain supporting Christ. The original 5th-century apse mosaic of the Santa Sabina was replaced by a very similar fresco by Taddeo Zuccari in 1559. The composition probably remained unchanged: Christ flanked by male and female saints, seated on a hill while lambs drinking from a stream at its feet. All three mosaics had a similar iconography.

6th-century pieces are rare in Rome but the mosaics inside the triumphal arch of the basilica of San Lorenzo fuori le mura belong to this era. The Chapel of Ss. Primo e Feliciano in Santo Stefano Rotondo has very interesting and rare mosaics from the 7th century. This chapel was built by Pope Theodore I as a family burial place.

A floor mosaic excavated at the

Great Palace of Constantinople, dated to the reign of

Justinian IIn the 7-9th centuries Rome fell under the influence of Byzantine art, noticeable on the mosaics of Santa Prassede, Santa Maria in Domnica, Sant'Agnese fuori le Mura, Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, Santi Nereo e Achilleo and the San Venanzio chapel of San Giovanni in Laterano. The great dining hall of Pope Leo III in the Lateran Palace was also decorated with mosaics. They were all destroyed later except for one example, the so-called Triclinio Leoniano of which a copy was made in the 18th century. Another great work of Pope Leo, the apse mosaic of Santa Susanna, depicted Christ with the Pope and Charlemagne on one side, and SS. Susanna and Felicity on the other. It was plastered over during a renovation in 1585. Pope Paschal I (817-824) embellished the church of Santo Stefano del Cacco with an apsidal mosaic which depicted the pope with a model of the church (destroyed in 1607).

The fragment of an eighth-century mosaic, the Epiphany is one of the very rare remaining pieces of the medieval decoration of Old St. Peter's Basilica, demolished in the late 16th century. The precious fragment is kept in the sacristy of Santa Maria in Cosmedin. It proves the high artistic quality of the destroyed St. Peter's mosaics.

Byzantine mosaics

See also: Early Byzantine mosaics in the Middle East

Mosaics were more central to Byzantine culture than to that of Western Europe. Byzantine church interiors were generally covered with golden mosaics. Mosaic art flourished in the Byzantine Empire from the 6th to the 15th century. The majority of Byzantine mosaics were destroyed without trace during wars and conquests, but the surviving remains still form a fine collection.

The great buildings of Emperor Justinian like the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, the Nea Church in Jerusalem and the rebuilt Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem were certainly embellished with mosaics but none of these survived.

Important fragments survived from the mosaic floor of the Great Palace of Constantinople which was commissioned during Justinian's reign. The figures, animals, plants all are entirely classical but they are scattered before a plain background. The portrait of a moustached man, probably a Gothic chieftain, is considered the most important surviving mosaic of the Justinian age. The so-called small sekreton of the palace was built during Justin II's reign around 565-577. Some fragments survive from the mosaics of this vaulted room. The vine scroll motifs are very similar to those in the Santa Constanza and they still closely follow the Classical tradition. There are remains of floral decoration in the Panagia Acheiropoietos Church in Thessaloniki (5-6th centuries).

In the 6th century, Ravenna, the capital of Byzantine Italy, became the center of mosaic making. Istria also boasts some important examples from this era. The Euphrasian Basilica in Parentium was built in the middle of the 6th century and decorated with mosaics depicting the Theotokos flanked by angels and saints.

Fragments remain from the mosaics of the Church of Santa Maria Formosa in Pola. These pieces were made during the 6th century by artists from Constantinople. Their pure Byzantine style is different from the contemporary Ravennate mosaics.

A pre-

Iconoclastic depiction of St. Demetrios at the Aghios Demetrios Basilica.

Very few early Byzantine mosaics survived the Iconoclastic destruction of the 8th century. Among the rare examples are the 6th-century Christ in majesty (or Ezekiel's Vision) mosaic in the apse of the Osios David Church in Thessaloniki that was hidden behind mortar during those dangerous times. The mosaics of the Hagios Demetrios Church, which were made between 634 and 730, also escaped destruction. Unusually almost all represent Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki, often with suppliants before him.

In the Iconoclastic era, figural mosaics were also condemned as idolatry. The Iconoclastic churches were embellished with plain gold mosaics with only one great cross in the apse like the Hagia Irene in Constantinople (after 740). There were similar crosses in the apses of the Hagia Sophia Church in Thessaloniki and in the Church of the Dormition in Nicaea. The crosses were substituted with the image of the Theotokos in both churches after the victory of the Iconodules (787-797 and in 8-9th centuries respectively, the Dormition church was totally destroyed in 1922).

A similar Theotokos image flanked by two archangels were made for the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople in 867. The dedication inscription says: "The images which the impostors had cast down here pious emperors have again set up." In the 870s the so-called large sekreton of the Great Palace of Constantinople was decorated with the images of the four great iconodule patriarchs.

The post-Iconoclastic era was the heyday of Byzantine art with the most beautiful mosaics executed. The mosaics of the Macedonian Renaissance (867-1056) carefully mingled traditionalism with innovation. Constantinopolitan mosaics of this age followed the decoration scheme first used in Emperor Basil I's Nea Ekklesia. Not only this prototype was later totally destroyed but each surviving composition is battered so it is necessary to move from church to church to reconstruct the system.

An interesting set of Macedonian-era mosaics make up the decoration of the Hosios Loukas Monastery. In the narthex there is the Crucifixion, the Pantokrator and the Anastasis above the doors, while in the church the Theotokos (apse), Pentecost, scenes from Christ's life and ermit St Loukas (all executed before 1048). The scenes are treated with a minimum of detail and the panels are dominated with the gold setting.

Detail of mosaic from

Nea Moni Monastery

The Nea Moni Monastery on Chios was established by Constantine Monomachos in 1043-1056. The exceptional mosaic decoration of the dome showing probably the nine orders of the angels was destroyed in 1822 but other panels survived (Theotokos with raised hands, four evangelists with seraphim, scenes from Christ's life and an interesting Anastasis where King Salomon bears resemblance to Constantine Monomachos). In comparison with Osios Loukas Nea Moni mosaics contain more figures, detail, landscape and setting.

Another great undertaking by Constantine Monomachos was the restoration of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem between 1042 and 1048. Nothing survived of the mosaics which covered the walls and the dome of the edifice but the Russian abbot Daniel, who visited Jerusalem in 1106-1107 left a description: "Lively mosaics of the holy prophets are under the ceiling, over the tribune. The altar is surmounted by a mosaic image of Christ. In the main altar one can see the mosaic of the Exhaltation of Adam. In the apse the Ascension of Christ. The Annunciation occupies the two pillars next to the altar."[2]

The Daphni Monastery houses the best preserved complex of mosaics from the early Comnenan period (ca. 1100) when the austere and hieratic manner typical for the Macedonian epoch and represented by the awesome Christ Pantocrator image inside the dome, was metamorphosing into a more intimate and delicate style, of which The Angel before St Joachim — with its pastoral backdrop, harmonious gestures and pensive lyricism — is considered a superb example.

The 9th and 10th-century mosaics of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople are truly classical Byzantine artworks. The north and south tympana beneath the dome was decorated with figures of prophets, saints and patriarchs. Above the principal door from the narthex we can see an Emperor kneeling before Christ (late 9th or early 10th century). Above the door from the southwest vestibule to the narthex another mosaic shows the Theotokos with Justinian and Constantine. Justinian I is offering the model of the church to Mary while Constantine is holding a model of the city in his hand. Both emperors are beardless - this is an example for conscious archaization as contemporary Byzantine rulers were bearded. A mosaic panel on the gallery shows Christ with Constantine Monomachos and Empress Zoe (1042–1055). The emperor gives a bulging money sack to Christ as a donation for the church.

The dome of the Hagia Sophia Church in Thessaloniki is decorated with an Ascension mosaic (c. 885). The composition resembles the great baptistries in Ravenna, with apostles standing between palms and Christ in the middle. The scheme is somewhat unusual as the standard post-Iconoclastic formula for domes contained only the image of the Pantokrator.

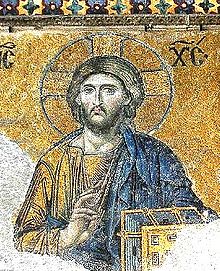

Mosaic of

Christ Pantocrator from

Hagia Sophia from the

Deesis mosaic.

There are very few existing mosaics from the Komnenian period but this paucity must be due to accidents of survival and gives a misleading impression. The only surviving 12th-century mosaic work in Constantinople is a panel in Hagia Sophia depicting Emperor John II and Empress Eirene with the Theotokos (1122–34). The empress with her long braided hair and rosy cheeks is especially capturing. It must be a life-like portrayal because Eirene was really a redhead as her original Hungarian name, Piroska shows. The adjacent portrait of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos on a pier (from 1122) is similarly personal. The imperial mausoleum of the Komnenos dynasty, the Pantokrator Monastery was certainly decorated with great mosaics but these were later destroyed. The lack of Komnenian mosaics outside the capital is even more apparent. There is only a "Communion of the Apostles" in the apse of the cathedral of Serres.

A striking technical innovation of the Komnenian period was the production of very precious, miniature mosaic icons. In these icons the small tesserae (with sides of 1 mm or less) were set on wax or resin on a wooden panel. These products of extraordinary craftmanship were intended for private devotion. The Louvre Transfiguration is a very fine example from the late 12th century. The miniature mosaic of Christ in the Museo Nazionale at Florence illustrates the more gentle, humanistic conception of Christ which appeared in the 12th century.

The sack of Constantinople in 1204 caused the decline of mosaic art for the next five decades. After the reconquest of the city by Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1261 the Hagia Sophia was restored and a beautiful new Deesis was made on the south galery. This huge mosaic panel with figures two and a half times lifesize is really overwhelming due to its grand scale and superlative craftsmanship. The Hagia Sophia Deesis is probably the most famous Byzantine mosaic in Constantinople.

The Pammakaristos Monastery was restored by Michael Glabas, an imperial official, in the late 13th century. Only the mosaic decoration of the small burial chapel (parekklesion) of Glabas survived. This domed chapel was built by his widow, Martha around 1304-08. In the miniature dome the traditional Pantokrator can be seen with twelve prophets beneath. Unusually the apse is decorated with a Deesis, probably due to the funerary function of the chapel.

The Church of the Holy Apostles in Thessaloniki was built in 1310-14. Although some vandal systematically removed the gold tesserae of the background it can be seen that the Pantokrator and the prophets in the dome follow the traditional Byzantine pattern. Many details are similar to the Pammakaristos mosaics so it is supposed that the same team of mosaicists worked in both buildings. Another building with a related mosaic decoration is the Theotokos Paregoritissa Church in Arta. The church was established by the Despot of Epirus in 1294-96. In the dome is the traditional stern Pantokrator, with prophets and cherubim below.

The greatest mosaic work of the Palaeologan renaissance in art is the decoration of the Chora Church in Constantinople. Although the mosaics of the naos have not survived except three panels, the decoration of the exonarthex and the esonarthex constitute the most important full-scale mosaic cycle in Constantinople after the Hagia Sophia. They were executed around 1320 by the command of Theodore Metochites. The esonarthex has two fluted domes, specially created to provide the ideal setting for the mosaic images of the ancestors of Christ. The southern one is called the Dome of the Pantokrator while the northern one is the Dome of the Theotokos. The most important panel of the esonarthex depicts Theodore Metochites wearing a huge turban, offering the model of the church to Christ. The walls of both narthexes are decorated with mosaic cycles from the life of the Virgin and the life of Christ. These panels show the influence of the Italian trecento on Byzantine art especially the more natural settings, landscapes, figures.

The last Byzantine mosaic work was created for the Hagia Sophia, Constantinople in the middle of the 14th century. The great eastern arch of the cathedral collapsed in 1346, bringing down the third of the main dome. By 1355 not only the big Pantokrator image was restored but new mosaics were set on the eastern arch depicting the Theotokos, the Baptist and Emperor John V Palaiologos (discovered only in 1989).

In addition to the large-scale monuments several miniature mosaic icons of outstanding quality was produced for the Palaiologos court and nobles. The loveliest examples from the 14th century are Annunciation in the Victoria and Albert Museum and a mosaic diptych in the Cathedral Treasury of Florence representing the Twelve Feasts of the Church.

In the troubled years of the 15th century the fatally weakened empire could not afford luxurious mosaics. Churches were decorated with wall-paintings in this era and after the Turkish conquest.

Rome in the High Middle Ages

Apse mosaic in the

Santa Maria MaggioreThe last great period of Roman mosaic art was the 12-13th century when Rome developed its own distinctive artistic style, free from the strict rules of eastern tradition and with a more realistic portrayal of figures in the space. Well-known works of this period are the floral mosaics of the Basilica di San Clemente, the façade of Santa Maria in Trastevere and San Paolo fuori le Mura. The beautiful apse mosaic of Santa Maria in Trastevere (1140) depicts Christ and Mary sitting next to each other on the heavenly throne, the first example of this iconographic scheme. A similar mosaic, the Coronation of the Virgin, decorates the apse of Santa Maria Maggiore. It is a work of Jacopo Torriti from 1295. The mosaics of Torriti and Jacopo da Camerino in the apse of San Giovanni in Laterano from 1288-94 were thoroughly restored in 1884. The apse mosaic of San Crisogono is attributed to Pietro Cavallini, the greatest Roman painter of the 13th century. Six scenes from the life of Mary in Santa Maria in Trastevere were also executed by Cavallini in 1290. These mosaics are praised for their realistic portrayal and attempts of perspective. There is an interesting mosaic medaillon from 1210 above the gate of the church of San Tommaso in Formis showing Christ enthroned between a white and a black slave. The church belonged to the Order of the Trinitarians which was devoted to ransoming Christian slaves.

The great Navicella mosaic (1305–1313) in the atrium of the Old St. Peter's is attributed to Giotto di Bondone. The giant mosaic, commissioned by Cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi, was originally situated on the eastern porch of the old basilica and occupied the whole wall above the entrance arcade facing the courtyard. It depicted St. Peter walking on the waters. This extraordinary work was mainly destroyed during the construction of the new St. Peter's in the 17th century. Navicella means "little ship" referring to the large boat which dominated the scene, and whose sail, filled by the storm, loomed over the horizon. Such a natural representation of a seascape was known only from ancient works of art.

Sicily

The heyday of mosaic making in Sicily was the age of the independent Norman kingdom in the 12th century. The Norman kings adopted the Byzantine tradition of mosaic decoration to enhance the somewhat dubious legality of their rule. Greek masters working in Sicily developed their own style, that shows the influence of Western European and Islamic artistic tendencies. Best examples of Sicilian mosaic art are the Cappella Palatina of Roger II, the Martorana church in Palermo and the cathedrals of Cefalù and Monreale.

The Cappella Palatina clearly shows evidence for blending the eastern and western styles. The dome (1142-42) and the eastern end of the church (1143–1154) were decorated with typical Byzantine mosaics ie. Pantokrator, angels, scenes from the life of Christ. Even the inscriptions are written in Greek. The narrative scenes of the nave (Old Testament, life of Sts Peter and Paul) are resembling to the mosaics of the Old St. Peter's and St. Paul's Basilica in Rome (Latin inscriptions, 1154–66).

The Martorana church (decorated around 1143) looked originally even more Byzantine although important parts were later demolished. The dome mosaic is very similar to that of the Cappella Palatina with Christ enthroned in the middle and four bowed, elongated angels. The Greek incsriptions, decorative patterns, the evangelists in the squinches are obviously executed by the same Greek masters who worked on Capella Palatina. The mosaic depicting Roger II of Sicily, dressed in Byzantine imperial robes, receiving the crown by Christ was originally in the demolished narthex together with another panel, the Theotokos with Georgios of Antiochia, the founder of the church.

In Cefalù (1148) only the high, French Gothic presbytery was covered with mosaics: the Pantokrator on the semidome of the apse and cherubim on the vault. On the walls we can see Latin and Greek saints, with Greek inscriptions.

The Monreale mosaics constitute the largest decoration of this kind in Italy, covering 0,75 hectares with at least 100 million glass and stone tesserae. This huge work was executed between 1176 and 1186 by the order of King William II of Sicily. The iconography of the mosaics in the presbytery is similar to Cefalu while the pictures in the nave are almost the same as the narrative scenes in the Cappella Palatina. The Martorana mosaic of Roger II blessed by Christ was repeated with the figure of King William II instead of his predecessor. Another panel shows the king offering the model of the cathedral to the Theotokos.

The Cathedral of Palermo, rebuilt by Archbishop Walter in the same time (1172–85), was also decorated with mosaics but none of these survived except the 12th-century image of Madonna del Tocco above the western portal.

The cathedral of Messina, consecrated in 1197, was also decorated with a great mosaic cycle, originally on par with Cefalù and Monreale, but heavily damaged and restored many times later. In the left apse of the same cathedral 14th-century mosaics survived, representing the Madonna and Child between Saints Agata and Lucy, the Archangels Gabriel and Michael and Queens Eleonora and Elisabetta.

Southern Italy was also part of the Norman kingdom but great mosaics did not survive in this area except the fine mosaic pavement of the Otranto cathedral from 1166, with mosaics tied into a tree of life, mostly still preserved. The scenes depict biblical characters, warrior kings, medieval beasts, allegories of the months and working activity. Only fragments survived from the original mosaic decoration of Amalfi's Norman Cathedral. The mosaic ambos in the churches of Ravello prove that mosaic art was widespread in Southern Italy during the 11-13th centuries.

The palaces of the Norman kings were decorated with mosaics depicting animals and landscapes. The secular mosaics are seemingly more Eastern in character than the great religious cycles and show a strong Persian influence. The most notable examples are the Sala di Ruggero in the Palazzo dei Normanni, Palermo and the Sala della Fontana in the Zisa summer palace, both from the 12th century.

Mosaics in Venice

In parts of Italy, which were under eastern artistic influences, like Sicily and Venice, mosaic making never went out of fashion in the Middle Ages. The whole interior of the St Mark's Basilica in Venice is clad with elaborate, golden mosaics. The oldest scenes were executed by Greek masters in the late 11th century but the majority of the mosaics are works of local artists from the 12-13th centuries. The decoration of the church was finished only in the 16th century. One hundred and ten scenes of mosaics in the atrium of St Mark's were based directly on the miniatures of the Cotton Genesis, a Byzantine manuscript that was brought to Venice after the sack of Constantinople (1204). The mosaics were executed in the 1220s.

Other important Venetian mosaics can be found in the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Torcello from the 12th century, and in the Basilical of Santi Maria e Donato in Murano with a restored apse mosaic from the 12th century and a beautiful mosaic pavement (1140). The apse of the San Cipriano Church in Murano was decorated with an impressive golden mosaic from the early 13th century showing Christ enthroned with Mary, St John and the two patron saints, Cipriano and Cipriana. When the church was demolished in the 19th century, the mosaic was bought by Frederick William IV of Prussia. It was reassembled in the Friedenskirche of Potsdam in the 1840s.

Trieste was also an important center of mosaic art. The mosaics in the apse of the Cathedral of San Giusto were laid by master craftsmen from Veneto in the 12-13th centuries.

Medieval Italy and italian mosaics

The monastery of Grottaferrata founded by Greek Basilian monks and consecrated by the Pope in 1024 was decorated with Italo-Byzantine mosaics, some of which survived in the narthex and the interior. The mosaics on the triumphal arch portray the Twelve Apostles sitting beside an empty throne, evoking Christ's ascent to Heaven. It is a Byzantine work of the 12th century. There is a beautiful 11th-century Deesis above the main portal.

The Abbot of Monte Cassino, Desiderius sent envoys to Constantinople some time after 1066 to hire expert Byzantine mosaicists for the decoration of the rebuilt abbey church. According to chronicler Leo of Ostia the Greek artists decorated the apse, the arch and the vestibule of the basilica. Their work was admired by contemporaries but was totally destroyed in later centuries except two fragments depicting greyhounds (now in the Monte Cassino Museum). "The abbot in his wisdom decided that great number of young monks in the monastery should be thoroughly initiated in these arts" - says the chronicler about the role of the Greeks in the revival of mosaic art in medieval Italy.

In Florence a magnificiant mosaic of the Last Judgement decorates the dome of the Battistero. The earliest mosaics, works of art of many unknown Venetian craftsmen (including probably Cimabue), date from 1225. The covering of the ceiling was probably not completed until the 14th century.

The impressive mosaic of Christ in Majesty, flanked by the Blessed Virgin and St. John the Evangelist in the apse of the cathedral of Pisa was designed by Cimabue in 1302. It evokes the Monreale mosaics in style. It survived the great fire of 1595 which destroyed most of the mediveval interior decoration.

Sometimes not only church interiors but façades were also decorated with mosaics in Italy like in the case of the St Mark's Basilica in Venice (mainly from the 17-19th centuries, but the oldest one from 1270–75, "The burial of St Mark in the first basilica"), the Cathedral of Orvieto (golden Gothic mosaics from the 14th century, many times redone) and the Basilica di San Frediano in Lucca (huge, striking golden mosaic representing the Ascension of Christ with the apostles below, designed by Berlinghiero Berlinghieri in the 13th century). The Cathedral of Spoleto is also decorated on the upper façade with a huge mosaic portraying the Blessing Christ (signed by one Solsternus from 1207).

Western and Central Europe Mosaics

Carolingian mosaic in

Germigny-des-PrésBeyond the Alps the first important example of mosaic art was the decoration of the Palatine Chapel in Aachen, commissioned by Charlemagne. It was completely destroyed in a fire in 1650. A rare example of surviving Carolingian mosaics is the apse semi-dome decoration of the oratory of Germigny-des-Prés built in 805-806 by Theodulf, bishop of Orléans, a leading figure of the Carolingian renaissance. This unique work of art, rediscovered only in the 19th century, had no followers.

Only scant remains prove that mosaics were still used in the Early Middle Ages. The Abbey of Saint-Martial in Limoges, originally an important place of pilgrimage, was totally demolished during the French Revolution except its crypt which was rediscovered in the 1960s. A mosaic panel was unearthed which was dated to the 9th century. It uses somewhat incongruously cubes of gilded glass and deep green marble, probably taken from antique pavements. This could also be the case with the early 9th century mosaic found under the cathedral of Saint-Quentin, where antique motifs are copied but using only simple colours. The mosaics in the Cathedral of Saint-Jean at Lyon have been dated to the 11th century because they employ the same non-antique simple colours. More fragments were found on the site of Saint-Croix at Poitiers which might be from the 6th or 9th century.

Close up of the bottom left corner of the picture above. Click the picture to see the individual

tesseraeLater fresco replaced the more labor-intensive technique of mosaic in Western-Europe, although mosaics were sometimes used as decoration on medieval cathedrals. The Royal Basilica of the Hungarian kings in Székesfehérvár (Alba Regia) had a mosaic decoration in the apse. It was probably a work of Venetian or Ravennese craftsmen, executed in the first decades of the 11th century. The mosaic was almost totally destroyed together with the basilica in the 17th century. The Golden Gate of the St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague got its name from the golden 14th-century mosaic of the Last Judgement above the portal. It was executed by Venetian craftsmen.

A “painting” made from tesserae in

St Peter's Basilica,

Vatican State, Italy

The Crusaders in the Holy Land also adopted mosaic decoration under local Byzantine influence. During their 12th-century reconstruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem they complemented the existing Byzantine mosaics with new ones. Almost nothing of them survived except the "Ascension of Christ" in the Latin Chapel (now confusingly surrounded by many 20th-century mosaics). More substantial fragments were preserved from the 12th-century mosaic decoration of the Church of the Nativity in Betlehem. The mosaics in the nave are arranged in five horizontal bands with the figures of the ancestors of Christ, Councils of the Church and angels. In the apses the Annunciation, the Nativity, Adoration of the Magi and Dormition of the Blessed Virgin can be seen. The program of redecoration of the church was completed in 1169 as a unique collaboration of the Byzantine emperor, the king of Jerusalem and the Latin Church.[3]

In 2003, the remains of a mosaic pavement were discovered under the ruins of the Bizere Monastery near the River Mureº in present-day Romania. The panels depict real or fantastic animal, floral, solar and geometric representations. Some archeologists supposed that it was the floor of an Orthodox church, built some time between the 10th and 11th century. Other experts claim that it was part of the later Catholic monastery on the site because it shows the signs of strong Italianate influence. The monastery was situated that time in the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Renaissance and Baroque Mosaics

Although mosaics went out of fashion and were substituted by frescoes, some of the great Renaissance artists also worked with the old technique. Raffael's Creation of the World in the dome of the Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo is a notable example that was executed by a Venetian craftsman, Luigi di Pace.

During the papacy of Clement VIII (1592–1605), the “Congregazione della Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro" was established, providing an independent organisation charged with completing the decorations in the newly-built St. Peter's Basilica. Instead of frescoes the cavernous Basilica was mainly decorated with mosaics. Among the explanations are:

- The old St. Peter's Basilica had been decorated with mosaic, as was common in churches built during the early Christian era; the seventeenth century followed the tradition to enhance continuity.

- In a church like this with high walls and few windows, mosaics were brighter and reflected more light.

- Mosaics had greater intrinsic longevity than either frescoes or canvases.

- Mosaics had an association with bejeweled decoration, flaunting richness.

The mosaics of St. Peter's often show lively Baroque compositions based on designs or canvases from like Ciro Ferri, Guido Reni, Domenichino, Carlo Maratta, and many others. Raphael is represented by a mosaic replica of this last painting, the Transfiguration. Many different artists contributed to the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century mosaics in St. Peter's, including Giovanni Battista Calandra, Fabio Cristofari (d. 1689), and Pietro Paolo Cristofari (d. 1743).[4] Works of the Fabbrica were often used as papal gifts.

The Christian East Mosaic

Main article: Early Byzantine mosaics in the Middle East

Jerusalem on the

Madaba Map The eastern provinces of the Eastern Roman and later the Byzantine Empires inherited a strong artistic tradition from the Late Antiquity. Similarly to Italy and Constantinople churches and important secular buildings in Syria and Egypt were decorated with elaborate mosaic panels between the 5th and 8th centuries. The great majority of these works of art were later destroyed but archeological excavations unearthed many surviving examples.

The single most important piece of Byzantine Christian mosaic art in the East is the Madaba Map, made between 542 and 570 as the floor of the church of Saint George at Madaba, Jordan. It was rediscovered in 1894. The Madaba Map is the oldest surviving cartographic depiction of the Holy Land. It depicts an area from Lebanon in the north to the Nile Delta in the south, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the west to the Eastern Desert. The largest and most detailed element of the topographic depiction is Jerusalem, at the center of the map. The map is enriched with many naturalistic features, like animals, fishing boats, bridges and palm trees.

One of the earliest examples of Byzantine mosaic art in the region can be found on Mount Nebo, an important place of pilgrimage in the Byzantine era where Moses died. Among the many 6th-century mosaics in the church complex (discovered after 1933) the most interesting one is located in the baptistery. The intact floor mosaic covers an area of 9 x 3 m and was laid down in 530. It depicts hunting and pastoral scenes with rich Middle Eastern flora and fauna.

Mosaic floor from the church on

Mount Nebo (baptistery, 530)

The Church of Sts. Lot and Procopius was founded in 567 in Nebo village under Mount Nebo (now Khirbet Mukhayyat). Its floor mosaic depicts everyday activities like grape harvest. Another two spectacular mosaics were discovered in the ruined Church of Preacher John nearby. One of the mosaics was placed above the other one which was completely covered and unknown until the modern restoration. The figures on